Because Nothing Is Happening on the Screen

When we looked at the actual download speeds of the sites we tested, we found that there was no correlation between these and the perceived speeds reported by our users. About.com, rated slowest by our users, was actually the fastest site (average: 8 seconds). Amazon.com, rated as one of the fastest sites by users, was really the slowest (average: 36 seconds). — The Truth About Download Time

Was Jakob Nielsen, the usability guru, wrong when he concluded that to avoid annoying users, pages should load in less than 10 seconds? I think he’s still right because it is no fun staring at the hourglass for 5 minutes. But when we tell our friends that Flickr is faster than Picasa, we don’t say uploading a 1MB JPEG takes 2.35 seconds in Flickr while it takes 4.86 seconds in Picasa. We just say Flickr is faster.

What is missing from Nielsen’s conclusion is that when users say a website is slow, they talk about their feelings and not what they see in the stopwatch. This does not mean that programmers should abandon measuring website performance. We still need to make that slow function run faster and there is no way to tell if we are progressing or not if we don’t know the score.

Browsers follow a fetch-parse-flow-paint process to load web pages. Given a URL, the fetch engine finds it and stores the page into a cache. The parse engine discovers the various HTML elements and produces a tree that represents the internal structure of the page. The flow engine handles the layout while the paint engine’s job is to display the web page on the screen. Nothing unusual except that when the parse engine sees an image, it would stop and ask the fetch engine to read the image. The parse engine continues only after it has determined the image’s size. The end result is that the browser will wait until all the elements of the page has been processed before it shows the page. During this processing, all the user sees is a blank page. This is how things work with the 1st widely-used web browser, Mosaic.

Netscape Navigator 1.0 took a different approach. When the parse engine sees an image, it still asks the fetch engine to load the image. The difference is that the parse engine will put a placeholder in the internal structure of the page to mark where the image is and let the flow and paint engines do their job. When the image is loaded and analyzed, the paint engine does a repaint on the screen. This can happen several times if the page has a lot of images. If you measure the overall time it takes to finalize the page display, Mosaic is faster than Netscape. But, users would say otherwise. Mosaic lacks a sign of progress while the appearance of text, then an image, then another image makes users think that Netscape is faster.

My first encounter with the world wide web was in April 1996 while working as a student assistant at the Advanced Science Technology Institute. Back then, web pages consist mostly of text. Nowadays, it is not uncommon for a page to contain lots of big images, embedded videos, references to several CSS and JavaScript files. So while computing power and bandwidth has improved over the years, content has also bloated making performance issues still a problem.

The common opinion is that if you want to improve a website’s performance, you focus on the database, web server, and other back-end stuff. But, Yahoo! engineers found out that most optimization opportunities are present after the web server has responded with the page. When a URL is entered into the browser, 62% to 95% of the time is spent fetching the images, CSS, JavaScript contained in the page. It is clear that reducing the number of HTTP requests will also reduce response time.

The Yahoo! Exceptional Performance Group has identified 13 rules for making fast-loading web pages. The group’s lead, Steve Souders, has also written a book on website performance.

Another cool product from the team is YSlow (nice name). It analyzes a web page and tells you why it is slow based on the 13 rules. YSlow is a Firefox plugin and works alongside another web developer’s indispensable tool, Firebug. When I first used YSlow with SchoolPad, my initial grade was F (58). I first set out to address Rule #10 - Minify JavaScript. Since SchoolPad is written on Ruby on Rails, the asset_packager plugin came in handly in merging all my CSS files and JavaScript files. Using the plugin, CSS and JavaScript files can be used in a single reference.The asset_packager is also smart. During development mode where CSS and JavaScripts files are often updated, the plugin references the original script files but in production mode it uses the minified versions of your CSS and JS files. A few changes in your Capistrano file, then you can make the minification (is that a word?) process automatic every time you deploy your application. After a few more tweaks, my overall grade is now C (78) with an F on rules #2 (Use a CDN) and #3 (Add an expires header). I can’t address rule #2 because that requires money and #3 has to wait because it requires more Googling.

It might happen that you have an A in YSlow yet users complain that your website is slow. Talk about an unlucky day. Don’t despair. Maybe, it is time to focus on managing expectations instead of performance.

I wrote my first GUI-based program using Visual Basic on Windows 3.1. (I’m sure Evan would argue that Basic is not a programming language). Any Visual Basic book would tell you to change the mouse pointer to an hourglass before a lengthy operation such as a database query, and change it back to the default pointer afterwards.

Screen.MousePointer = vbHourglass

'Do lots of stuff.......

Screen.MousePointer = vbNormal

I think many people got addicted to the mouse pointer that along with the release of Windows 95 was a variety of themes that replace the default mouse pointer icon with a rocketship, a barking dog, or a wiggling clownfish.

Anyway, back to the web. Wait! The reason the hourglass is widely used in desktop applications is because it tells the user that the application has accepted the action, and it is now working on it. In your web apps, you should do the same.

Traditionally, when you click a link in a website, the browser sends a request to the server, receives a page, and repaints the content. Feedback in most browsers is in the form of a spinning logo at the top right part or an expanding strip at the bottom or at the status bar.

Here comes Ajax. With Ajax you can do away with refreshing everything and update only a portion of your page. Unlike the page-based model, the browser cannot give feedback that something is going on after an Ajax-based action. No more spinning logo. No more expanding strip bar. We went backward in interface design.

Fortunately, there is a way to give feedback that requires writing code using JavaScript. It could be as simple as writing a message “Loading…” on the page or using an animated GIF file. One implementation would be just to show a previously hidden text or image or create an ‘img’ element and append it to where you want to display (usually a ‘div’ element). Many web applications nowadays use various style of animation but the key idea is the same — a smoothly looping animation to indicate an activity.

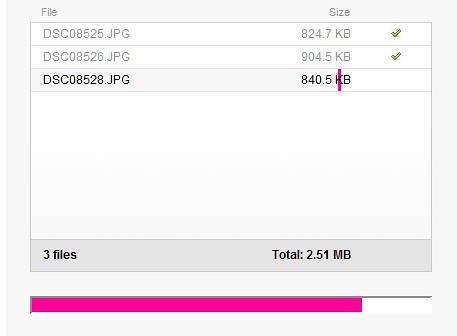

Animated activity indicators are useful for tasks that will incur short delays. If the delay takes too long, the user may think the application is going on circles or has become a zombie. For longer delays, it is best to show how much progress has been made, an estimate of time remaining, or a sequence of messages telling the user what’s happening at the present. This is very useful but tricky to implement because HTTP requests don’t give tracking information at regular intervals. If you are making a sequence of 4 requests, you can guesstimate that progress is 25% done when the 1st call has completed. Flickr uses the best activity indicator I’ve seen so far when uploading images. Image files are usually big and Flickr does a great job of giving progress feedback to its users — an overall progress and a per-file progress indicator.

During the modem days, it is acceptable that many sites are slow given the hardware limitation. But now in the broadband era, amplified by tons of marketing, users expect websites to be lightning fast.

Nobody wants a slow website. But when the user say it is slow, oftentimes, it is because nothing is happening on the screen.